The other sections of ChemHAT show how chemical production heavily contributes to health problems in exposed workers and in communities. So, why are we discussing heat and heat illness prevention?

There are two primary reasons:

- Heat, like chemical exposures, is often an under-recognized and poorly controlled workplace hazard.

- Current chemical production processes and the poor control of emissions significantly contribute to greenhouse gas pollution which causes climate change. Because of this, the manufacture and release of many chemicals contribute to the cycle of extreme seasonal temperatures, flooding, and a number of other weather-related disasters, that particularly overwhelms individuals with chronic health problems, outdoor workers, the elderly, and other more vulnerable people.

In the US, heat causes more deaths than any other weather hazard including devastating hurricanes, floods, or extreme cold(1). An August 2021 analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data shows that worker heat deaths have doubled since the early 1990s(2). As heat-related deaths increase, more needs to be done to protect workers in the states and territories of the US. New rules need to address the disproportionate impact of heat stress on Latines who have suffered one-third of all heat fatalities since 2010 but make up only 17% of the U.S. workforce(3).

As we saw in 2021 with a historic heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, climate change is touching parts of the world that are unprepared and under-resourced to solve these issues. In late June, the heat wave contributed ---meaning, it either caused or made another illness worse --- to over 150 injury deaths over a three-week period in the state of Washington alone(4).

Climate Change and its impact on workers and the population at large.

Many indoor workers, such as factory and warehouse workers, are at risk of heat exhaustion or stroke due to hazardous working conditions in some cases, and a lack of safety measures in others. In 2022, Reynaldo Mota Frias, a 42-year-old Amazon warehouse worker, died during one of the hottest Julys on record in New Jersey. in an area of the warehouse known to be hot and have poor air circulation. Amazon blamed Reynaldo’s death on a “personal medical condition,” and then installed a new air conditioning system weeks later.

In 2018, Jordan MacNair, a 19-year-old football player on track to play professionally, collapsed during an outdoor workout with his team while running sprints. He had a body temperature of 106 degrees when he arrived at a nearby hospital. Jordan eventually succumbed to his injuries and died. The training and coaching staff didn’t recognize the signs of heat stress and didn’t provide him with immediate shade or any cool-down methods including after his teammates expressed concern.

This tragedy speaks to the real dangers of heat stress as our climate continues to heat up. More people will have to know and recognize the warning signs to protect themselves and their loved ones. The CDC has labeled athletes as a population that is disproportionately affected by extreme heat along with children, outdoor workers, seniors, low-income households, and individuals with chronic medical conditions(6).

As climate change increasingly impacts workers' health and the quality of their jobs, safety and health advocates have pushed for implementing state and federal OSHA heat standards to protect workers at risk of heat injury and illness in indoor and outdoor work environments. As our summers continue to get hotter, and as unusual, strong, and persistent heat waves batter vulnerable communities, workers are at risk of collapsing and getting killed if protections are not in place(5).

A comprehensive and protective OSHA heat standard that will serve both indoor and outdoor workers affected by heat would be a big help. Currently, a proposed rule for a federal heat standard is in limbo, but states can create their own heat standard.

Until we get a strong federal rule states can use the existing California, Oregon, and Washington outdoor heat standards and Minnesota's indoor heat standards along with the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) or NIOSH’s heat stress and strain recommendations to build their own comprehensive standard that empowers workers authorizes workers to protect themselves and their co-workers.

Preventing Heat-Related Illnesses and Injuries

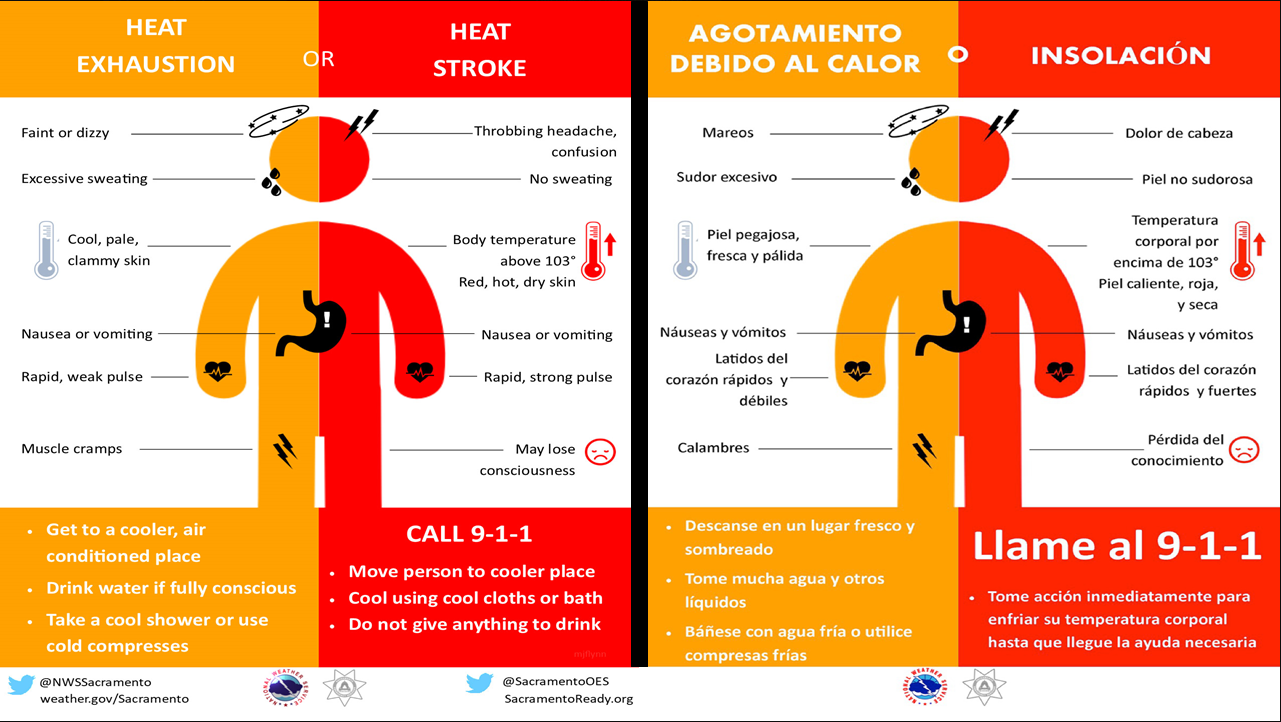

Some of the key signs someone is experiencing heat strain:

Source: Sacrementoready.org

For workers looking to advocate for heat stress policy, programs, or legislation, learn the signs of heat stress and get in touch with your union or an organization focused on these issues like the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. These types of organizations can help you, or put you in touch with the right organization, to form a safety and health committee, a group focused on improving working conditions through health and safety programs and operational changes, and help you develop and implement a strategic plan to hold your employer accountable for reducing the hazards of heat exposure, and implementing the needed controls.

Here is a starting list of tasks, and resources that can help workers and their representatives get started advocating for heat-related protections and controls. Work with your local union or consider joining one to gather more resources and build the power you need to better protect workers from heat stress:

Familiarize yourself with the NIOSH Recommendations for Reducing Heat Stress:

Install air conditioning or fans to cool off workers, or use reflective or heat-absorbing barriers, and install dehumidifiers to reduce humidity. Push for the use of engineering controls that follows the hierarchy of controls. Engineering controls like the use of A/C are prioritized over administrative controls and PPE due to the reliability and efficiency of engineering controls. *Note: Above certain temperatures, fans have the opposite effect because they blow hot air on people and make environmental conditions warmer.

Limit time in the heat (e.g. plan work according to sun direction at different times of the day; start work early or late to avoid extreme temperatures), use tools intended to make the job less strenuous or difficult, use a heat alert program, and use a buddy system.

Train supervisors to identify and warn workers of heat stress potential on hot days. Workers should be trained on first aid for heat stress, and how to use and care for heavy clothing and equipment that causes workers to be hotter than usual.

Gradually increase workers’ time in hot conditions over a 2-week period, and closely supervise new employees during this period. Advocate for a heat stress acclimatization program so workers have adequate time to acclimate and get trained to identify and prevent heat-related injuries.

Employers should provide cool (59°F), and safe-to-drink water for workers, and place it close to them. Workers should also be encouraged to stay hydrated and to consider drinking sports drinks if sweating lasts for several hours.

Workers should be encouraged and ensured appropriate rest breaks to cool down and hydrate. Employers should shorten work periods and increase the number and length of rest periods in cool-down areas, especially during heavy work shifts and in extreme conditions

The Heat Injury and Illness Prevention Work Group of the National Advisory Committee on Occupational Safety and Health (NACOSH) produced and presented a set of recommendations and best practices for a heat exposure control plan, also known as a Heat Illness Prevention Plan, to federal OSHA. Many of the NACOSH recommendations align with the protective requirements of the state rules listed below and throughout the Heat section on ChemHAT, but the primary purpose of these recommendations is to identify what triggers an action in a workplace, detail who is in charge of certain response tasks, and how to address it while satisfying federal and state Hazard Communication (HAZCOM) rules.

The NACOSH group provided recommendations on how workers and supervisors should be trained, as well as recommendations on how environmental monitoring should take place, additional workplace controls like required water breaks and clear guidance on what is considered a safe place to rest, and more, including: For your convenience, we highlighted a few of the key recommendations that build off of the state requirements listed in the STATE HEAT STRESS RULES section on ChemHAT.

- The Heat Illness Prevention plan should be regularly re-evaluated and updated at least annually, and after adverse events such as the onset and reporting of symptoms, or the seeking of medical attention.

- To protect workers who are working alone, supervisors should check in regularly with their supervisees and know their specific location in case of emergencies. This can be planned and communicated during a morning safety meeting or check-in along with any other important notes regarding health and safety protections.

- Example: Delivery drivers also have check-ins with supervisors when workers have to self-monitor due to heat hazards

- The plan should include planning for foreseeable events growing in frequency and other emergencies. One example is wildfire smoke, which may require more workers to rely on PPE which increases the risk of heat-related hazards.

- To ensure workers’ heat burden is being monitored accurately, both temperatures and heat indexes should be monitored, not one or the other, during shifts.

- Monitoring response plans, or the detailed action steps for responding to a high heat index or burden, should be written for each specific worksite and communicated to workers.

- Workers must be authorized and supported to participate in monitoring, learn the measurement approaches being used in their workplaces, can self-monitor, and be able to respond appropriately

- Adjust for heat waves by observing weather data and ensure workers have enough time to acclimate to the new heat burden

Additional resources are in the section below:

Definitions: Below are key definitions for heat-related illness and prevention.

Acclimatization: Acclimatization is the process of your body adapting to repeated exposure to a hot environment. Improved sweating and cooling and the ability to work in hot environments at a lower core temperature and heart rate are examples of acclimatization

Heat Cramps: usually affect workers who sweat a lot during strenuous activity. This sweating depletes the body’s salt and moisture levels. Low salt levels in muscles cause painful cramps. Heat cramps may also be a symptom of heat exhaustion.

Heat Exhaustion: Heat exhaustion is the body’s response to an excessive loss of water and salt, usually through excessive sweating. Heat exhaustion is most likely to affect vulnerable populations like the elderly and people with high blood pressure who work in hot environments.

Common symptoms include heavy sweating, high body temperature, headache, nausea, dizziness, feeling weak, easily irritated, heavy sweating, elevated body temperature, decreased need to urinate

Heat Stroke: Heat stroke is the most serious heat-related illness. It occurs when the body can no longer control its temperature: the body’s temperature rises rapidly, the sweating mechanism fails, and the body is unable to cool down. When heat stroke occurs, the body temperature can rise to 106°F or higher within 10 to 15 minutes. Heat stroke can cause permanent disability or death if the person does not receive emergency treatment.

Heat Syncope: Heat syncope is a fainting (syncope) episode or dizziness that usually occurs when standing for too long or suddenly standing up after sitting or lying. Factors that may contribute to heat syncope include dehydration and lack of acclimatization.

PPE Heat Burden: The increased risk for heat-related illnesses caused by wearing PPE (e.g. waterproof aprons, respirators, surgical caps, additional layers of clothing, gloves, etc.).

Rhabdomyolysis (rhabdo) is a medical condition associated with heat stress and prolonged physical exertion. Rhabdo causes the rapid breakdown, rupture, and death of muscle. When muscle tissue dies, electrolytes and large proteins are released into the bloodstream. This can cause irregular heart rhythms, seizures, and damage to the kidneys.

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT): A measure of potential heat stress while also accounting for environmental factors such as air temperature, sunlight exposure, humidity, radiant heat, wind speed, sun angle, and cloud cover.

Resources:

NIOSH Heat Stress (Home Page)

NACOSH – Final Heat Work Report

NIOSH – Criteria for a Recommended Standard

CDC Extreme Heat

CDC Heat Tracker

OSHA Heat Illness Prevention – Publications

OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool App

OSHA Case Studies

CPWR – Overall Heat-Illness Prevention Program Checklist for Construction

CPWR – Daily Heat-Illness Prevention Checklist for Construction

NACOSH (OSHA)

National COSH – Toolkit

- National COSH – Beat the Heat Worker Demands

- Signs of Heat Stress, Heat Exhaustion and Heat Stroke

- Know Your Rights / Demand Heat Protections at Work (Bilingual)

- Nine Steps for Taking Action in the Workplace

- Heat Illness at Work: Know the Facts-Demand Protection (Available in 16 languages)

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety – Hot Environments – Control Measures

UFCW3000 – Safety and Workers’ Rights in Extreme Heat Situations

Public Citizen – The Impact of Heat Stress on Workers of Color

NIOSH & OSHA Factsheets:

NIOSH – Work/Rest Schedule

NIOSH – Acclimatization

NIOSH – Hydration

OSHA – Protecting Workers from the Effects of Heat

References:

1. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics. Weather fatalities 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.weather.gov/hazstat/

2. Shipley J et al. 2021. Heat is killing workers in the U.S. — _and there are no federal rules to protect them. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/08/17/1026154042/hundreds-of-workers-have-died…

3. Ibid

5. Philip SY, et al. 2021. Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heatwave on the Pacific Coast of the US and Canada June 2021.

https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/wp-content/uploads/NW-US-extrem…

6. CDC Extreme Heat (2023) https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/extremeheat/index.html